By Peter Fullbrook, Founder, Prosell

Research tells us that classroom sales training (whether it be real or virtual) is only appropriate for 15% of development needs (Rummler 1995). Not only does this cause concern about the use and abuse of sales training events, it also raises the tantalising question of what is appropriate if training is not?

The broad answer is workplace rather than classroom development. To explore this more closely, the researchers seem to indicate that regular interaction, rather than one off events, leads to enhanced skills and increased performance.

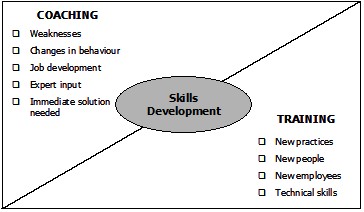

The diagramme opposite has been created as a result of applying a range of performance improvement techniques to varying organisations over a 20-year period (www.prosell.com). It indicates that with a “clean sheet of paper” (i.e. no preconceptions or bad habits, as with new starters or new roles), people can more easily accept, in a sales training environment, that specific skills and approaches are correct and need to be mastered.

With individuals that already have a perception of what is right and wrong and in some cases extremely entrenched opinions, a different approach needs to be used. Not only do we need to explain why new skills are needed, we also need to sensitively reassure people that they and their (old) skills are not redundant, but need to be adapted and updated. If we are attempting to change behaviour, as opposed to initiating it, coaching is shown to be a more effective tool.

In order to develop further the rationale for this model and the positioning of sales coaching, we need to be familiar with the relationship between management intervention and performance/behaviour change.

The US organisation Technikron conducted research into the level of intervention needed to drive behavioural change. (Technikron work with performance measurement and feedback systems in contact centres. The research was conducted in 1997.)

They concluded that to change behaviour the manager needed to interact with the individual, on average, 2-3 times a week. This raises serious concerns about the effectiveness of more traditional performance management tools, such as annual appraisal and performance reviews (Appraisals – A Good Investment? Prosell Research, 1993).

Whereas we accept that most good managers talk to their people more often than just at appraisal time, our experience tells us that this is not a series of regular interactions which are carefully planned to reinforce changes in behaviour and provide input (coaching), when needed.

Coaching also has greater impact in terms of immediacy of resolution and as such, should be a primary development tool.

Danger of re-training

There seems to be growing evidence that organisations accept that people will go through the same training (level and subject matter) at regular intervals (apart from compliance training). This implies a number of unhealthy traits within the organisation:

- there is no consequence for not applying skills in the workplace; and

- people can take away and/or apply as much or as little as they like.

Once this becomes accepted practice it also has an impact on the quality of training delivered. If people are not measured in their application of what they have learnt, then the training does not need to ensure comprehension, let alone competence.

The other major implication is centred on who is nominated for training in the first place. Research suggests that the primary reason for training is performance discrepancy or skill weakness. Those with skill weaknesses or areas for obvious development are not those who implement training well and willingly in the workplace. There is clear evidence that, “those who need it most use it least” (Dettaman and Steinberg, 1993).

Questions must therefore, be raised about both the economics of re-training and the validity of the practice.

The Skill Development model and its implications

The model opposite shows that individuals go through three stages when acquiring skills. Typically, the first and last stages, those of awareness and application, are workplace activities and in the main, management responsibilities.

The two figures on the left hand side of the model illustrate important points. The 35%-40% marks the point where people end up after training (on a competence scale of 1%–100%). This means that the majority of the acquisition of competence takes place in the workplace.

This is broadly accepted within the training fraternity. Whereas training allows people to explore new ways of doing things and hopefully exposes them to “best practice”, it does not create experts.

If expertise is acquired in the workplace and not the classroom, then we must accept that specific things need to happen in the workplace. Primarily, people need to be coached and given feedback on their competence.

Our 20 years experience tells us that, proportionately, the following time and effort needs to be expended to successfully take an individual through the skill development process:

- Awareness 25%

- Practice 35%

- Application 40%

The second figure (5%-9%) is where the research tells us people end up if nothing is done in the application phase. This is typically between unconscious incompetence and conscious incompetence. This typically happens with 4 – 5 months. This is a startling figure and perhaps explains why many people in business have a cynical view of the value of training. It seems they are right. Without specific application strategies, companies are wasting between 91 and 95 cents of every dollar they spend on training.

Practice and Feedback

It is commonly understood that people develop skills through one primary mechanism, practice and feedback. Conventional training tends to be squeezed for time and it is inevitably the practice sessions that are sacrificed. Too much content and not enough practice creates uncertainty in application, through issues of confidence and competence. If a person cannot, through practice, feedback and practice again, achieve a point of competence (“I have practiced this to the point where I feel competent to do it in the workplace”), they have no confidence in applying skills. The implications of this are that many people (over 75% in one study) actually avoid applying skills trained because they have no confidence that they will be effective. Those organisations that use coaching as a development tool do not seem to face these issues.

Near and Far Learning

Noted behavioural scientists, Detterman and Steinberg, published a book in 1996 entitled Transfer on Trial. The book focused on the issue of learning transfer (the measurable transfer of learning and skills from classroom to workplace). Their research had concluded that 86% of training did not transfer effectively. There were a variety of reasons for this – measurement, support, feedback (all key components of coaching). They also spoke about the difference between near and far learning as a critical issue.

Far learning means completing exercises which are broad, generic and explore our understanding of principles. Detterman and Steinberg’s research concluded that people found it difficult to relate broad principles to specific work situations – and as a result did not apply skills effectively.

Near learning produces significantly better results. Near learning is practicing the specific skills needed, through customised and intelligently constructed exercises, so that the individual is practicing exactly what they are being asked to do in the workplace. Coaching is the ultimate example of near learning – it says to the individual, “We are going to practice this until you feel you are doing it effectively and then evaluate as you do it live”. As a result it is significantly more effective in ensuring learning transfer.

Performance Management and Coaching

Performance management practices (appraisal, review, goal setting, etc) all become uncomfortable, bureaucratic exercises if those responsible cannot add value and direction through coaching. If neither party feels value is being added by the other, then both parties view the process as lacking in worth and tend to avoid it.

This also is reflected in a more serious deficiency that is commonly observed in management practice. If a manager cannot rectify a performance deficiency they seem to imply that this is not their responsibility but solely that of the individual.

These situations end up with a management style of “I point out your weaknesses and you have to fix them”. If one considers the fact that research tells us that the main reason people leave jobs is dissatisfaction with the way in which they are managed (Institute of Directors, UK survey, 1989), then managers’ inability to coach and develop may be having a much more serious impact.

Conversely, a good coach does more than just coach. In order for a coach to be effective they must have a reasonable grasp of:

- Performance management;

- Motivation;

- Counselling;

- Development and support;

- Evaluation and feedback;

- Performance measurement;

- Goal setting and KPI management.

Feedback also tells us that competent coaches add value to staff and have much better relationships with their people. Creating a competent coach therefore, also creates competency in a number of essential areas.

References

Douglas Detterman and Robert Steinberg, Transfer on Trial: Intelligence, Cognition and Instruction, Ablex Publishing, 1993

Geary Rummler and Alan Brache, Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space in the Organisation Chart, 2nd ed, Jossey Bass, San Francisco, 1995.

Peter Fullbrook is the founder of Prosell and Managing Director of Prosell Pty Ltd, an international organisation that specialises in improving performance in workgroups through workplace based interventions.

Peter has been invited to speak by organizations such as the International Society for Performance Improvement, The Australian Institute of Management and the Australian Telecom Users Group Conference and has had a number of articles published.

- Prosell offers a program that combines sales training and sales coaching. It is based on recognised research, which tells us that training alone has limited impact and that when supported by skilful coaching, has 74% more chance of being implemented.

- Prosell has resources to deliver these programs across Australia, covering Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, Adelaide and Canberra.